Previously on the Persistence of Meow-mory, Maya and Ursula went back in time to New York City in 1948. Maya interviewed three wet cats about their lousy time working with Salvador Dali and Philippe Halsman while creating Dali Atomicus. Ursulina Bearham passed out from fright and dreamed the cats were attacking. A plan for revenge was hatched.

As Maya Dulcinea de Quintana Roo sized up the rickety fire escape, she thought about Don Quixote and how he went into battle without thinking about his safety.

When she was a puppy, her mother would tell her the story of the brave Don Quixote and his fight against the terrible windmills. Maya didn’t know what a windmill was. Her mother thought it was some sort of tornado monster, perhaps the same one that made thunder.

“Wouldn’t it be nice to be Don Quixote?” she thought. “So courageous. So sure of right and wrong.”

Then she realized her boss, Ursulina Bearham, was barking at her.

“Pay attention! I’m telling you the plan!”

“Sorry,” Maya said.

“Right,” Ursulina said. “We’ll go up this fire escape,” She leaped up and pulled down the ladder.

“And we’ll perch on that ledge right there,” Ursalina pointed a long way up. “Then we’ll go in that window.”

“That’s awfully high,” Maya said.

“Do you want to help these cats or not?”

“I do, but can’t we just go in the front and knock on the apartment door?”

“And then what?” Ursulina asked.

Maya wasn’t sure. She licked her paw and smoothed her ear.

“The thing is, Maya…if we just knock on the door and say,” Pretty please, Sir, may I have your lunch? “They aren’t just going to hand it over.”

“I know that.” Maya rolled her eyes.

'“But if we look through the window, we can do some reconnaissance, refine our plan, and steal the lunch. To do that, we must go up this fire escape.”

“Okay,” Maya said quietly.

“You don’t have to think about it, Maya. You just have to do it.”

Maya nodded.

“Let’s go!” Ursulina barked.

Ursulina bounded up the fire escape, with Maya skittering behind her.

Maya’s paws slipped through the grating here and there, and once, her paw jammed down hard, which really hurt, but she never lost her footing. Soon, she found that she was standing next to Ursulina on the 5th-floor landing.

Ursulina started to climb onto the ledge, but her back paws slipped out behind her, and she got stuck. She lay on her belly with her front half on the ledge, her rump hanging over the railing, and her back paws floating in space.

“A little help?” Ursulina asked.

Maya put her shoulder to Ursulina’s rump and pushed.

“Ursulina,” Maya grunted, “I think we need a squire.”

Ursulina made it onto the ledge, and Maya leaped up beside her.

Then she looked down.

“Don’t look down,” Ursulina said.

The cars in the street below blurred into colorful blobs. Maya could hear her heartbeat.

“I forgot how to breathe,” Maya said.

“No, you didn’t.”

“If we fall…” Maya said.

“We’re not going to fall.” Ursulina tutted. “It’s just like a sidewalk.”

Maya leaned into the wall and followed Ursulina along the ledge. Ursulina walked along the ledge with quick, precise steps that belied her fluffy exterior.

“How will we know which apartment is the right one?” Maya asked.

“Leave that to me.”

They made their way to the open window. Ursulina poked her head in.

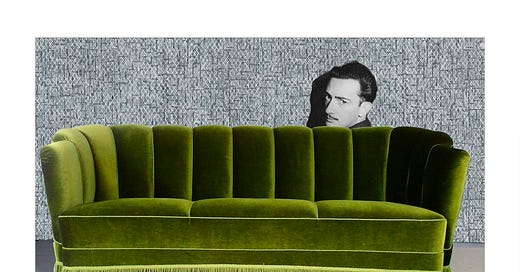

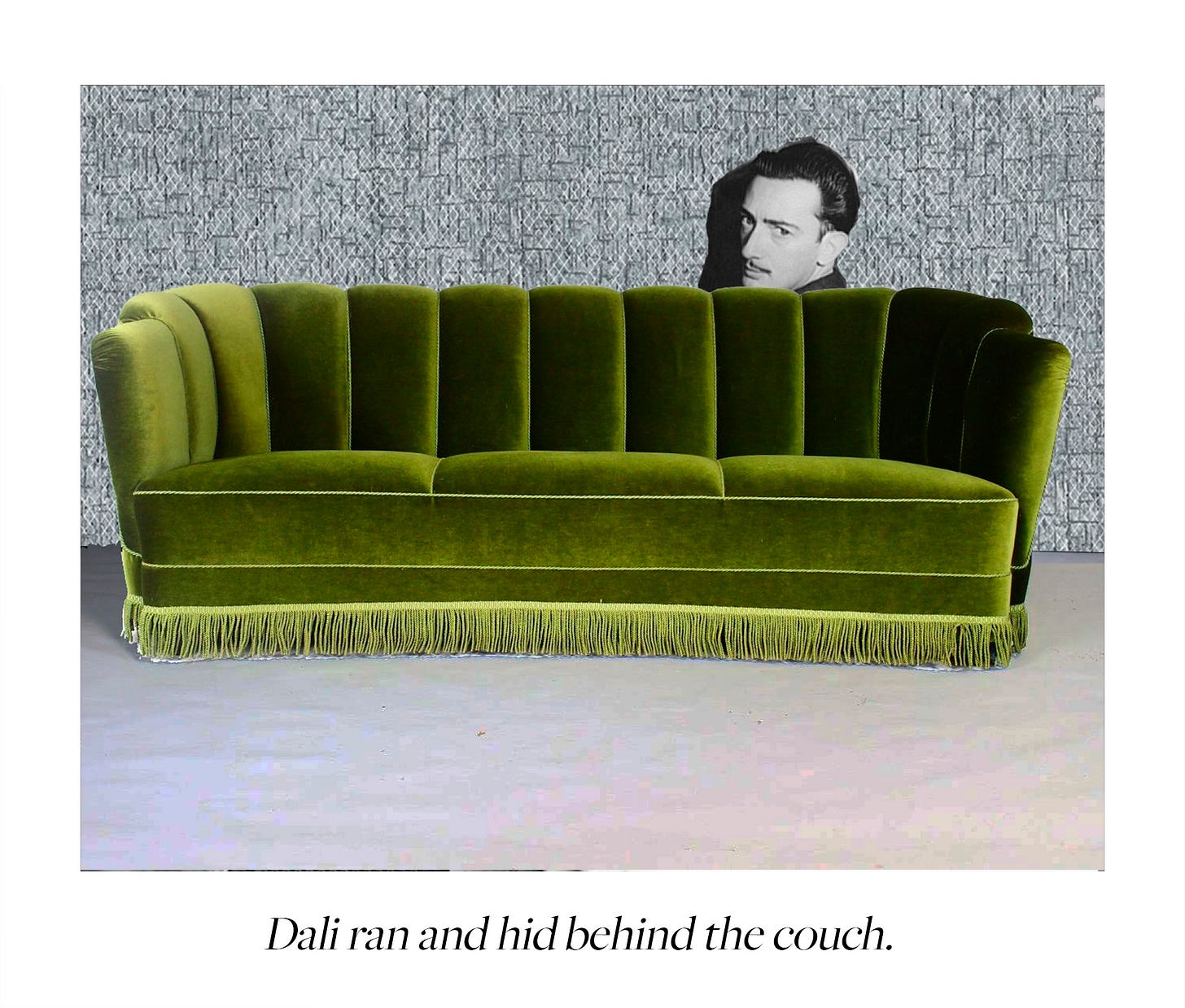

Inside, the apartment was sleek and modern. A green velvet couch hunkered down in the living room. A large radio was on the opposite wall, and a record player sat beside it.

To her right, she could see a closed door. Straight ahead, through a set of open double doors, was the kitchen.

A thin man with a waxed mustache sat at the kitchen table, frowning at some forks and spoons.

“I think I see Dali,” Ursulina whispered.

Then she heard the door to her right open. Ursulina ducked out of view.

She sniffed. She smelled sulfur dioxide and chlorine.

“Ah!” Ursulina thought, “like a photo lab.”

“Maya, this is the right window!” Ursulina whispered.

“That’s good,” Maya said, her voice a thin thread.

Maya sat on the ledge with her back against the wall. She kept her eyes closed. The bricks were warm against her back.

“As long as I feel the bricks, I’m not falling,” she said.

“You’re worrying about nothing,” Ursulina said, annoyed. “You’re as nimble as a cat.”

Maya opened her eyes, surprised at her boss’s kind compliment.

“Do you think so?” Maya asked.

“Yes. Now, listen closely. There are some portraits in that room. When the coast is clear, we’ll hide.”

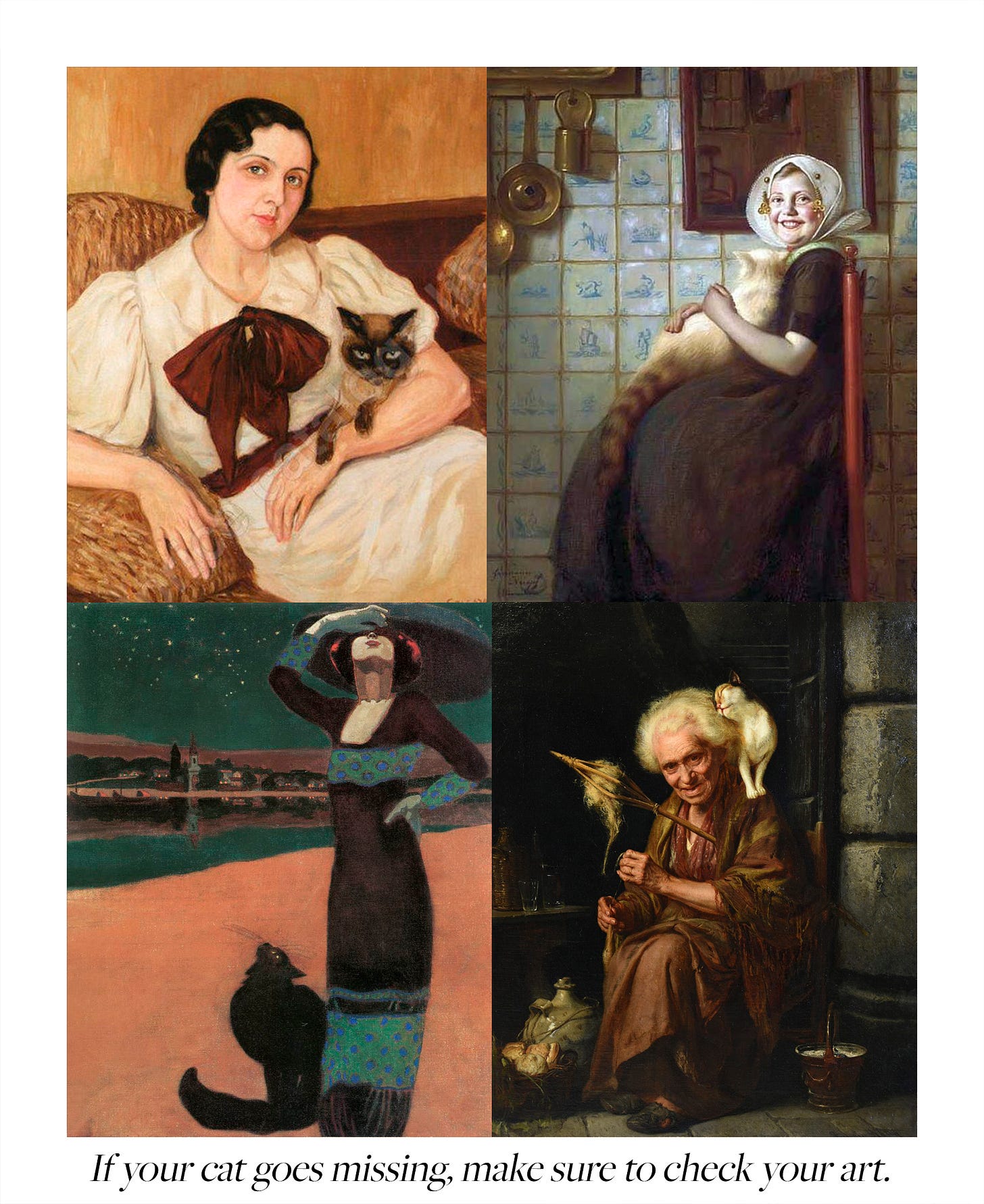

A little-known fact about animals is that they can hide in any picture or painting. The sneakiest ones can conceal themselves in a sculpture. If your cat goes missing, make sure to check your art. They like the soft laps of the past.

Maya whispered, “Don Cat-Otey.”

Ursulina watched from the window as the smelly man talked to Dali.

“Listen,” the smelly man said. “I’ve got more work to do before lunch. Can I trust you to buzz in the delivery man? “

“Si claro, of course,” Dali said.

“Are you all right?” The smelly man asked.

“I’m fine.”

“You look worried,” the smelly man said.

“Where did you get these spoons, Philippe? I don’t like them.”

“They were my grandmother’s,”

“Do you have any others? These are offending to me.”

The smelly man, Philippe Halsman, sighed.

“Sorry. That’s all I’ve got.”

Ursulina pulled her head from the window and leaned against the brick wall. She heard Halsman lock the darkroom door behind him.

“Come on.” She whispered.

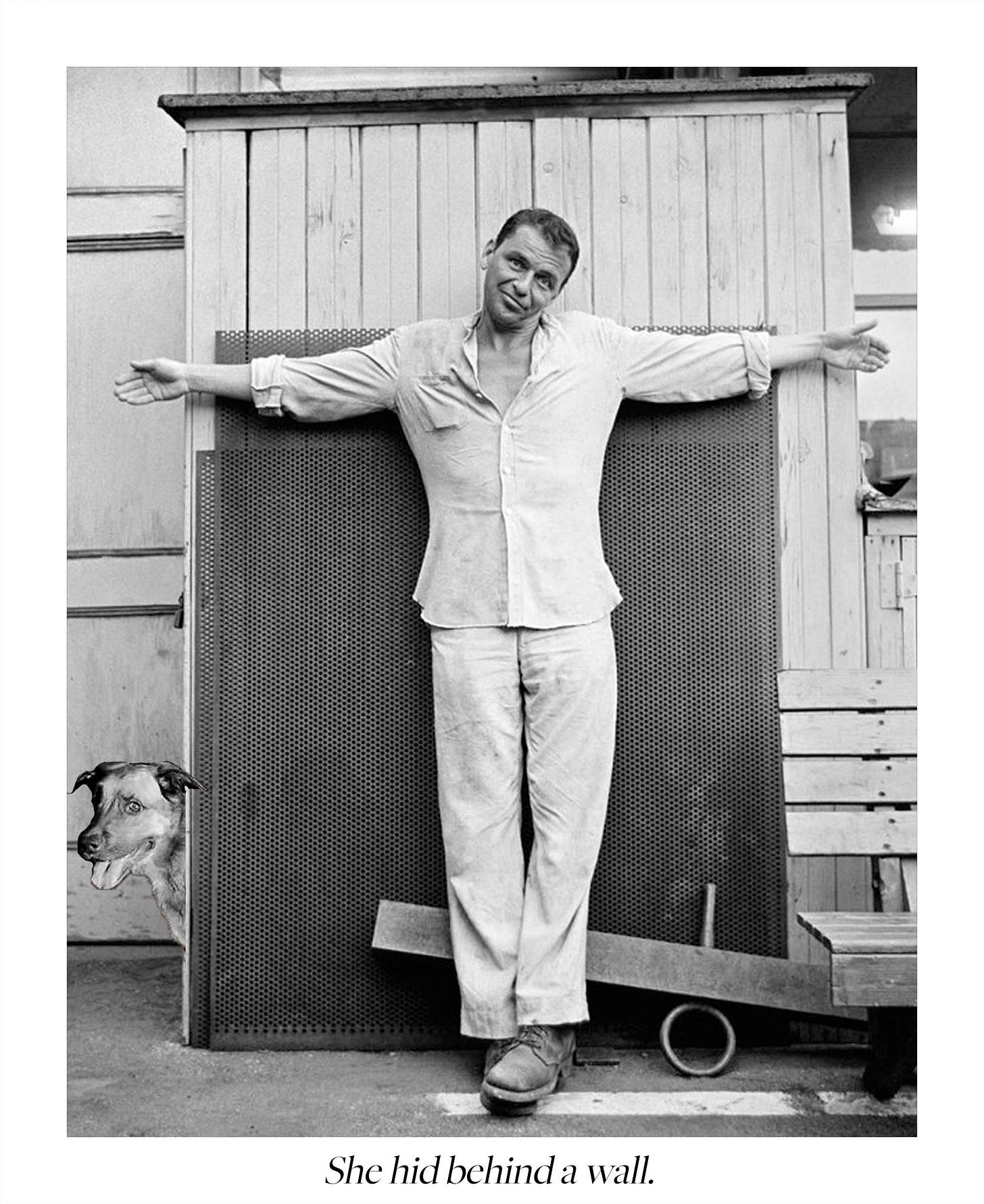

Ursulina and Maya stepped through the window. Ursulina jumped into a picture with Frank Sinatra. She hid behind a wall.

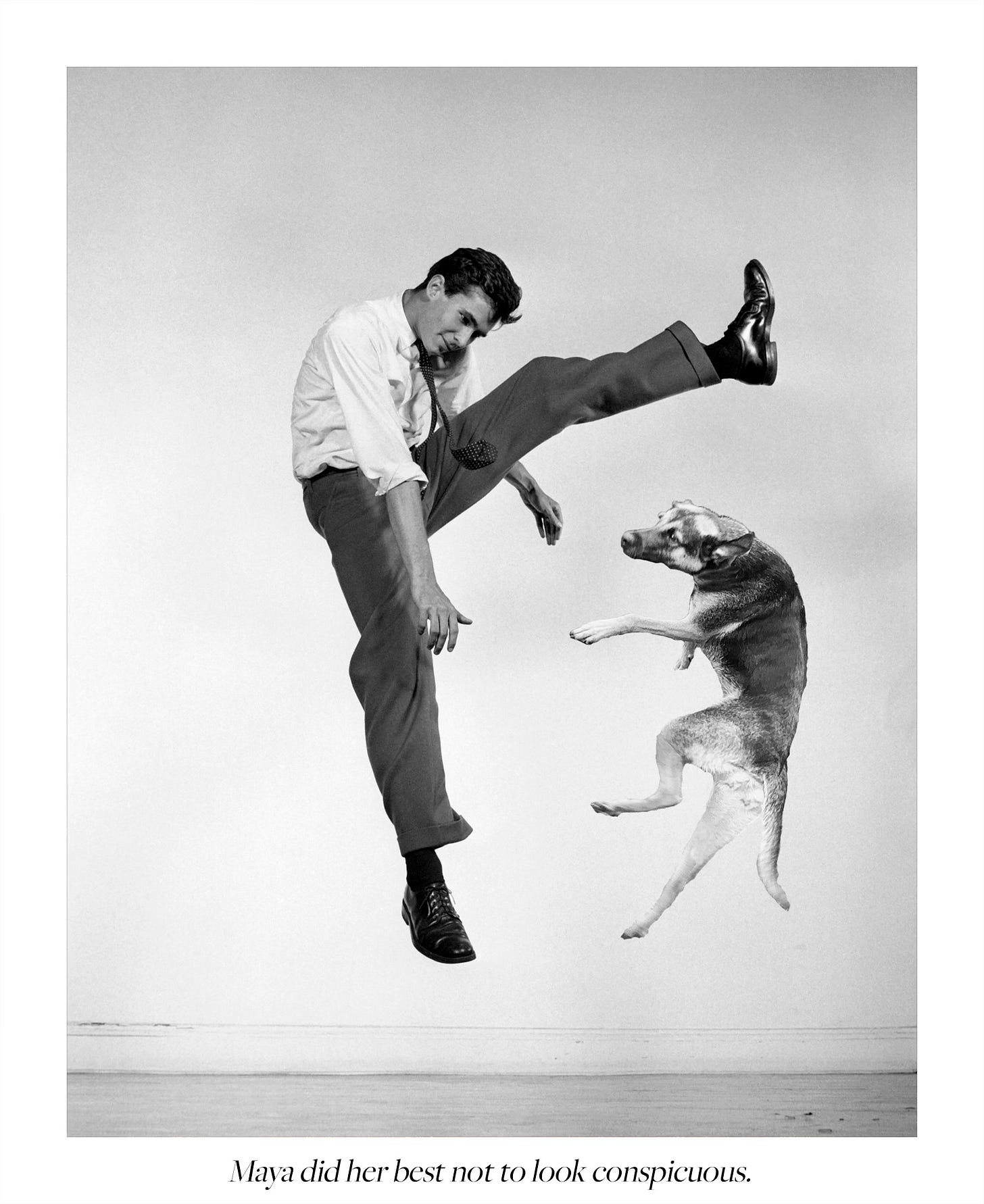

Maya ran across the room and jumped into the first frame she saw.

Then she realized the picture was just a man leaping into the air. With nothing to hide behind, Maya did her best not to look conspicuous.

Dali took a drag on his cigarette and said, “I will turn my back, and you will not sneak up on me.”

“Who is he talking to?” Maya asked.

“He’s looking at some spoons,” Ursulina whispered. “But I don’t see anyone else.”

Dali was famous for his Paranoic Critical Effect, a way to enter the dream space where he found his art. He’d stare at an object for twenty minutes or more until it moved independently, morphing into a skull or a woman or growing wings or teeth. Then he’d paint it.

Over time, the veil thinned. The objects started changing independently. A dead sardine would wiggle in Dali’s mouth, or a hard-boiled egg sitting in its egg cup would beat like a heart.

And now, the spoons were turning into snakes again and shaking their spoony heads at him.

Suddenly, there was a buzzing, angry sound, like a chainsaw grinding its way through a metal box. Dali covered his ears. The ash from his cigarette drifted to the floor.

Maya asked, “What do we do when the food comes?”

“We grab the food, and we run.”

“How are we getting out of the apartment?” Maya asked.

We exit the window in the kitchen and take the ledge over to the cat’s apartment on the other side.”

“What if the ledge doesn’t go all the way around?” Maya asked.

“Why wouldn’t it go all the way around?” Ursulina asked.

“I don’t know. I just don’t want to jump onto nothing.”

“You can’t think like that. When you leap, it will be there.”

Halsman walked out of the dark room. He didn’t notice the dogs in his pictures.

“Did you get our lunch?” He asked.

“No,” Dali said. “No. Philippe. There was a terrible sound.”

Halsman rushed out the apartment door.

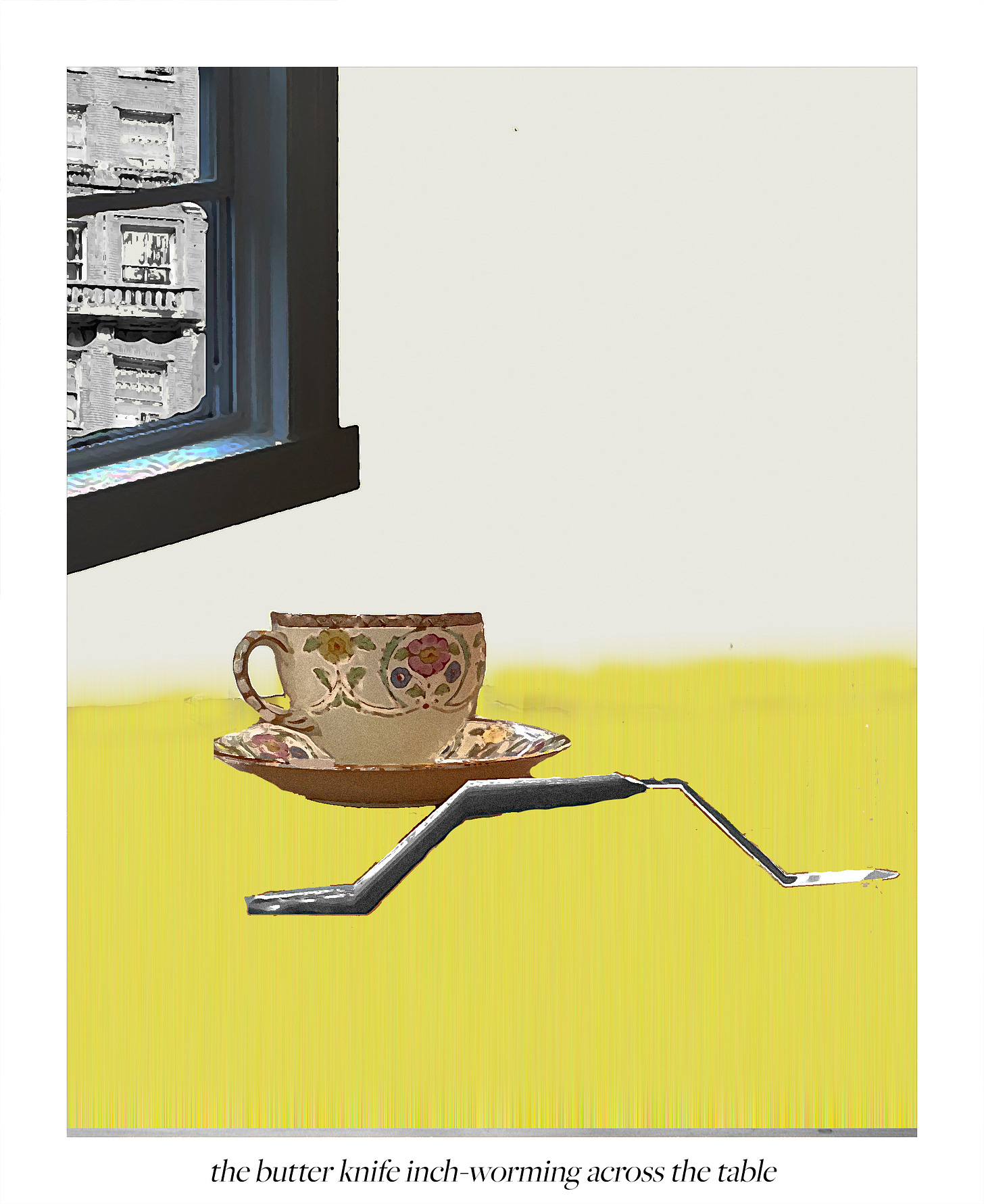

Dali saw a fork flip itself over and arch its back. The outer tines grew and separated into the front limbs of a praying mantis. The middle tines had curved around themselves, forming the mantis’ head.

Clack-clack went the mantis’ pincers. Click-click went the mantis’ jaw.

“I’ll bite your head off!” The fork said.

Dali grabbed the forks and spoons and tossed them out the window.

Then Dali saw the butter knife inch-worming across the table, making its getaway.

“What is he doing?” Maya asked.

“He’s throwing silverware out the window,” Ursulina answered.

He picked up the knife and tossed it out the window, too.

“Hey!” a man yelled. “You could have killed me.”

The man was burly. He wore a white T-shirt. Dali could see a tattoo on the man’s arm, but he couldn’t tell what it was. Had he been closer, he would have seen that it was a hula girl.

The man reminded Dali of the fishermen back home at the Gulf of Roses.

“Forgive me, Sir. It was either me or you.” Dali shouted. “And I am Dali.”

The man erupted in a colorful retort.

Dali shut the window and slunk away to the living room.

He looked at the picture of the jumping man. Maya held very still.

“I see you there,” he said.

Maya looked at him. She made a fierce face.

She shouted, “Be Nice To Cats!”

Dali ran and hid behind the couch.

There was a jingle of keys and the sound of a lock opening. Phillipe walked in and set two white take-out bags on the kitchen table.

“Dali?” he called out. “Salvador, lunch is here!”

Philippe opened the cupboard and pulled out two plates. He had talked with himself about his friend’s genius and endeavored to be more patient with Dali.

Dali came out from behind the couch and slouched in the kitchen doorway.

“Where’s the silverware?” Philippe asked.

Dali said nothing. He avoided eye contact.

“They were acting strange,” Dali explained. “The forks were especially dangerous.”

“What did you do?” Philippe shouted.

“I threw them out the window.’

Philippe opened the window in time to watch a car run over a spoon.

Philippe ran out of the apartment.

“Watch out for the man,” Dali called after him.

“Are you ready?” Ursulina asked.

“Born ready,” Maya answered.

Maya and Ursulina carefully stepped out of the frame and casually entered the kitchen.

Dali clapped his hands.

“Why hello, clever dogs! Dali greeted them. “I mean you no harm, my friends.”

He patted Ursulina on the head.

“Good doggy,” he said.

Ursulina wagged her tail and looked up into Dali’s eyes. She distracted Dali, acting the part of a perfect dog, a happy labrador mutt, here for pets and love.

Maya grabbed a lunch bag with her mouth and made it to the window. She was the first to jump out.

Her feet touched down on the concrete. She set the bag down and breathed a sigh of relief.

Ursulina casually sniffed at the remaining bag.

“Do you want my lunch?” Dali asked. He offered the bag to her.

Ursulina took the bag and walked to the window. She turned around and nodded goodbye. She wished he could understand the language of a dog because this would have been a great time to say something like, “See you around, Sally.”

Ursulina jumped through the window but overshot the ledge with her front feet.

She stood straight up. She yelped and teetered, her back toes gripping the concrete edge.

Maya grabbed Ursulina’s collar in her mouth and tried with all her might to pull her back. For a second, it seemed that they might both go over, and then Ursulina fell backward, landing on her rump and smashing Maya’s head into the wall.

Maya saw stars, then shook it off.

“Good catch, girl,” Ursulina said, though her words were mumbles due to the take-out bag in her mouth. “That was precarious!”

“After you,” Maya said, picking up her lunch bag.

Dali poked his nose out the window.

“Where are you going?” he asked. “I want to go too.” He climbed onto the ledge behind them.

“Hurry!” Ursulina shouted.

They high-tailed it to the far end of the building. Turning the corner, Ursulina saw a green curtain billowing out the open window just ahead of them. They leaped through the window, startling three cats.

Two arched and hissed.

The other one, Oscar, asked, “Is that lunch?”

Dali didn’t realize how high up he was. He saw the cars down below. He saw Philippe in the street, talking to the fisherman, who was gesturing up at the window.

“Philippe!” Dali called out.

Philippe looked up.

“Dali! What are you doing?” Philippe shouted.

“My doggy friends jumped out the window. I am going to find them.”

“Stay there, Salvador!”

Philippe and the fisherman ran inside.

Dali shrugged. Then he started scooting along the ledge.

The dogs ripped open the lunch bags. They found a whole lobster, plus warm rolls and butter pats. They found a wet package of fresh oysters in ice. They found fried fish filets.

The cats tucked in.

Ursulina watched the cats, and when she felt they were sufficiently distracted, she grabbed a few fish filets off the stack and shoved them in her mouth.

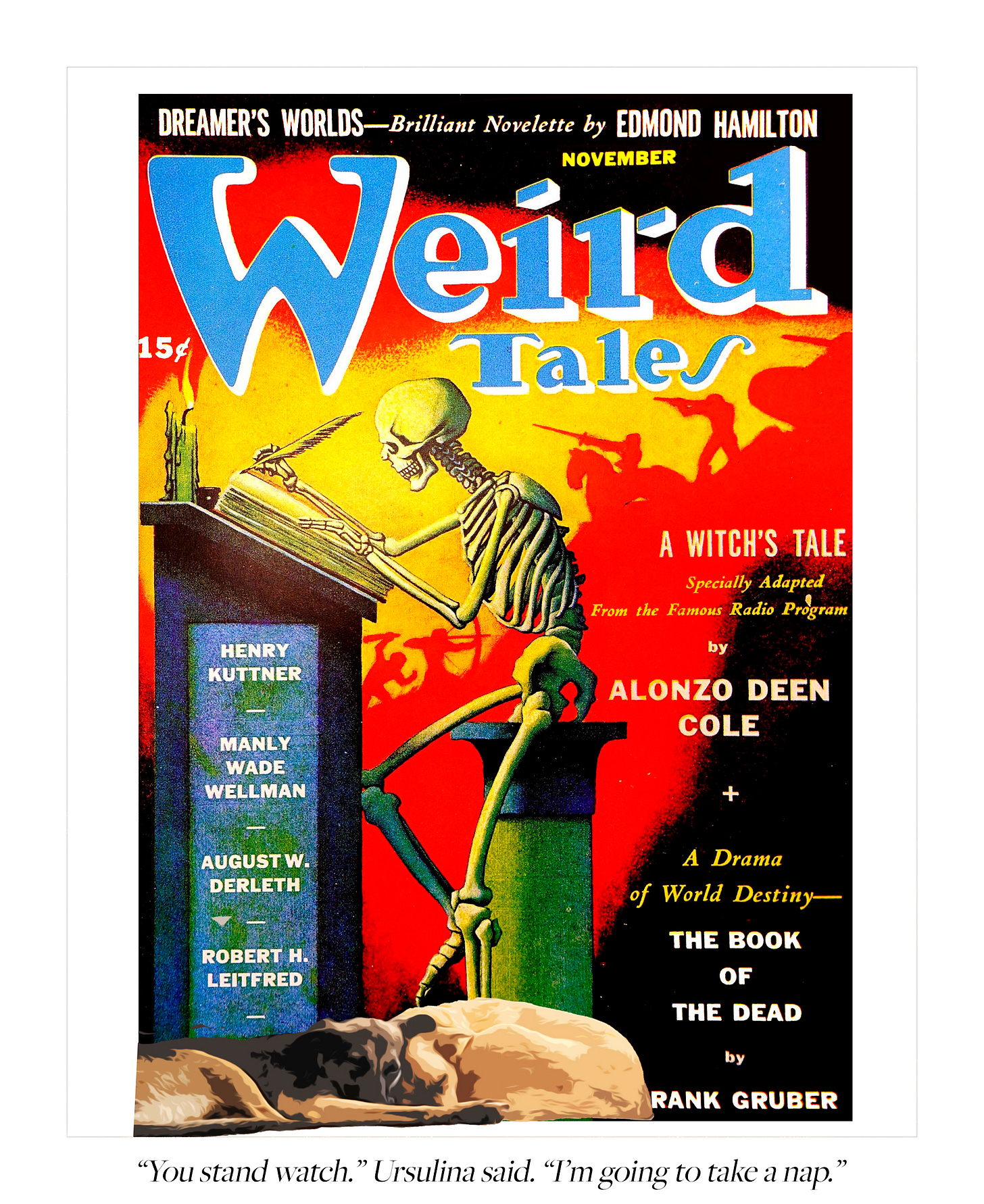

Ursulina saw a magazine on the table. It was titled “Wierd Tales.”

“Let’s hide in that magazine until the coast is clear,” Ursulina said.

She scarfed down a roll.

Then Maya and Ursulina settled in under the skeleton on the cover.

“You stand watch,” Ursulina said. “I’m going to take a nap.”

Maya let out an annoyed sigh.

“What’s wrong now?” Ursulina asked.

“I’m upset that Dali wasn’t angry about us stealing his lunch,” Maya said. “He didn’t care at all.”

“We’re not done with him,” Ursulina said. “And we made your cat friends happy, right?”

Maya saw Dali stick his head in the window.

“Cats,” he said. “Have you seen two dogs come by here?”

The cats hissed and snarled.

Dali frowned.

“A simple no would have sufficed,” he sniffed.

He slumped his shoulders and continued his sideways shuffle around the building.

Later, Maya slipped out of the magazine and picked through the remains of the lunch. She ate a few scraps of fish and the leftover lobster. Then she cleaned up the evidence, tossing the remains out the window.

“Hey!” She heard a man yell. Under the streetlight, she saw a man that reminded her of the sailors in Cancun. He had a tattoo of a hula girl.

The cats had curled up on the bed and fallen asleep with full bellies.

Maya leaned over them and sniffed deeply. The cats smelled damp and stinky, and their breath was fishy. This was the closest Maya had ever come to a cat, and it was thrilling.

“Sleep well,” she whispered.

Maya crawled back into the magazine and thought about the day’s adventure. Tomorrow, they would steal Manet’s Tėte du Bob.

She watched the shadows grow along the wall and saw the streetlights illuminate the building across the street.

“Goodnight, Mother, wherever you are,” she said. And then she fell asleep.

Her mother, fourteen years in the future, cocked her ear and listened.

“Goodnight, sweet girl,” she said. Then Marcella Dorotea de Quintana Roo took a diamond bracelet off an oil heiress’ vanity and slipped it into her pocket.